|

It was the summer of 2001 and I was almost finished my mechanized infantry platoon commander’s course, or Phase IV Infantry. To have a bit of fun, my course staff decided to set a few of us up on a joke ‘mission.’ The Phase III Infantry course , which was the dismounted infantry platoon commander’s course (and the staff), were just down the road in a defensive position. The Phase IV staff split a few of us into small patrols, gave us some CS gas grenades, and told us to pay a visit to both the Phase III students and staff later that night.

|

For those unfamiliar with CS gas, it’s a riot control agent. It’s not lethal, but it can (almost always does) cause a burning sensation in the eyes, nose, mouth and throat, to the point where someone subjected to it is pretty much incapacitated. And by incapacitated, I mean imagine that a skunk sprayed you square in the face. Fun times.

Anyhow, our patrols initially went fine, with my team easily infiltrating the camp with the Ph III staff. My problem was that I couldn’t find a good place to deploy my grenade and I was running out of time. With less than a few minutes left before my patrol was supposed to leave, I decided to post the grenade near the entrance of a tent. Even though I couldn’t see anyone, I figured the gas might linger and catch somebody that way.

Surprise, surprise – there were people in the tent. In their sleeping bags. Let’s just say they didn’t have a good night.

Later, in a blinding flash of the obvious while I was at the chow, it struck me that I probably didn’t come up with the best solution to the problem. (I may have been coached in that insight). I’d let time pressure me into doing something I hadn’t fully considered, as opposed to making a timely decision. Funnily enough, this is the next leadership principle we’ll examine with respect to writing.

Solve Problems and Make Timely Decisions

While the military has long recognized the leadership importance of making decisions, the understanding of how best to articulate this principle has evolved. For example, the earlier version of this CAF leadership principle was, ‘Make Sound & Timely Decisions.’ In hindsight, the new version is a big improvement as a principle that essentially says, ‘Make Good Decisions at the Right Time,’ is not particularly useful.

In terms of applicability, this principle is most easily found in combat situations. Amidst an environment that could be constantly morphing and is generally always confusing, combatants need to impose as much order as possible on the fog of war. This inevitably manifests through decisions. Alternatively, this process also happens at higher levels of thought, like in making strategy. Fundamentally, this is about thinking and it requires vigilance to ensure that decisions are made at the right times.

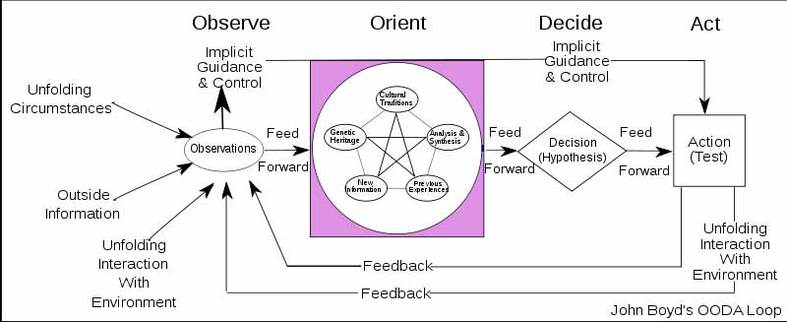

But the concept of time is relative and there’s a difference between making a timely decision and making decisions as fast as possible. Since John Boyd came up with his Observe-Orient-Decide-Act Loop (the OODA Loop), many in various military communities have been fixated in achieving decision-action supremacy by turning the OODA Loop faster and faster. This is a fallacy and ignores the fact that combat is an inherently interactive endeavour – there is always a thinking opponent.

|

Very quickly, Bruce Lee suggested that two fighters of equal ability would be likely to stalemate each other unless there was a big difference in speed. What’s more, the ebb and flow of the fight would take on a rhythm, with attack and defence assuming an almost harmonious and sequential relationship. If, however, one fighter could break the rhythm of the fight by striking on the half beat – something unexpected – they could catch the adversary off balance and impose their own cadence on the fight. Notably, this isn’t about speed; Bruce Lee even wrote that a fighter displaying excessive speed would simply catch up with the opponent’s parries.

|

he take away is that it’s the timing of decisions that matter, not the speed at which they’re made. So how to apply this to writing?

A writer still makes decisions that impact their ability to influence, either their small team or their readership. As an example, let’s look at how a writer decides to use their limited resources, in this case, time. Gabriela Pereira, in her book, DIY MFA, suggests that there are three major activities a writer has to:

The problem a writer is faced with is how much time and resources to devote to each activity. The more time spent writing, the better the book, but the less people who might actually read the book. The more time building a community, the better a writer’s network, but the less time doing core business or writing. You get the point. |

To solve this problem, a writer must be able to analyze their environment, come up with options, and determine the best way forward. In this case, there could be a number of different factors to consider, such as what ratio of activities is best or if the ratios should change given differing external factors. . For example, during the initial drafting stage of a novel, there could be a heavier weighting on writing, whereas the marketing stage for a finished book could have more emphasis on outreach. This isn’t rocket surgery, but they’re still critical decisions to address the problem of too few resources to accomplish all tasks.

What’s more, the writer must also consider when to adjust between activities, ideally adjusting ratios at the most opportune times. Hopefully this is something easy, like doing more outreach prior to a book launch, but it might also be more complex, like what type of outreach, what type of social media platforms to engage? Blogging? Paid advertising? All of these are effective to greater or lesser degrees, but can be impacted by the traits and skills of the author.

Aids to planning and decision making could even be incorporated, such as the concept of decisive points, or a decision support template. These aides automate the process somewhat, identifying certain conditions that when met, necessitate either a certain decision, or the automatic movement to the next stage. For example, when the line edit is done during the publishing stage, maybe the author automatically knows they need to move into a marketing mindset, which triggers reaching out for reviewers.

Interestingly, decisive points are just one small component of the larger process called campaign design, but isn’t that appropriate? What is taking a book from an imaginary idea to physical manifestation if not a campaign? Considering the manifest activities a writer can undertake – writing, reading, connecting with other writers – wouldn’t it be worthwhile to take a few moments to think things through? To have a campaign or a strategy?

Strategy is, after all, a process of defining a problem, coming up with options, then selecting a solution. Does a writer have a problem that requires options and solutions? If they’re serious, if they’re a professional, then yes, clearly. Sure, the problem the writer needs to solve might not be as life or death as whether to conduct a frontal assault versus a flanking (psst – flanking), but then again, lots of decisions are made in the military (or at least should be) that also aren’t as time pressing.

In the end, a writer is still going to face problems about what they do. They will still need to identify options to address those problems and make a decision about what option will best solve their problem. Sure, the problem may not be as exciting as whether to fire a CS gas grenade into a tent, but trust me, that’s probably all for the good.

For next week, we’ll apply the principle of ‘Direct, Motivate by Persuasion and Example, and by Sharing Risks and Hardships.’ A difficult one to apply, but not impossible.