|

Mostly…

At the same time, I was fortunate enough to be working for a general officer who cared about my development and made sure I was exposed to ideas, interactions, and processes that shaped my views and challenged my preconceptions. Yes, the drudgery of office work had to happen, after all, meetings don’t schedule themselves and senior leaders have (or at least should have) more important things to think about then how to set up a conference call. But even with all that, I still had time to leverage a unique opportunity to further my education and professional development and I’m a better officer for the experience. |

For the history buffs, I believe this principle used to be, ‘develop the leadership potential of your followers.’ It’s very close to the new version, but in the end, I like the additional clarity that comes in the updated definition for two reasons. First, I like that the focus is broader than just leadership potential. Although one could argue that leadership potential includes everything anyways, that argument strikes me as a bit too cute. Holistic leadership development entails so much, which suits the open-endedness of the current principle. Second, I like that development is augmented by education, but also with mentoring.

Mentorship is a huge component of military leadership development. Strangely, the concept hasn’t received much formal attention until only the last few years.

From a definition standpoint, mentorship is a professional relationship where a more experienced person voluntarily shares knowledge, insights, and wisdom with a less experienced person. It’s more than coaching, which is itself defined as a short-term relationship generally focused on specific skills and behaviours. Mentoring is typically longer term and more all-encompassing, addressing career, professional, and personal development. A mentor can variously be a teacher, a motivator, a guide, a counsellor, a sponsor, a coach, and a role model. Bottom line, it’s an enormous multiplier to leadership development.

There are a variety of types and forms of mentorship, from formal to informal mentoring, or group mentoring, and even reverse mentoring. This variety gives flexibility to accommodate the different needs and goals of those involved in the process.

While it’s clear what the mentee gets out of the relationship (actually the topic of a subsequent post) what about the mentor? What’s in it for them? Almost as much, including exposure to new ideas and perspectives, as well as an opportunity to reflect. As some might say, one of the best ways to confirm understanding of a subject matter is to have to teach it. Another important bonus of mentoring is the fostering of collaboration and community.

All great stuff, but how can this principle be applied to the business of writing?

To address the elephant in the room, clearly a new writer is not going to have the level of experience to provide a high level of mentorship. They’re still learning themselves, so what can they mentor somebody about? If it concerns the business of writing, maybe nothing.

But that doesn’t mean this is a dead end.

If the person in question happens to know a lot about a certain subject, say being a detective, maybe they can set up cross-functional mentoring with an author who writes criminal thrillers. In this case, they could leverage each other’s different backgrounds to learn from each other.

That aside, there are a number of attributes essential to being a good mentor that are also applicable to being a good writer, particularly in the area of outreach. Useful attributes for a mentor include: being an active listener, sharing realistic perspectives and experience, being non-judgemental, and being open to new ideas. These attributes are also incredibly useful for a writer in various circumstances, such as being part of a writer’s group or working with beta readers. Being able to give objective critique of other’s work, and being able to receive critique in return, is a difficult skill, but a valuable one to master.

More broadly, I’d offer that this principle is applicable to writing through an appeal to community and profession. Some of the reasons to conduct mentorship include passing on corporate memory, enhancing knowledge transfer, and bringing new individuals up to speed quickly. All of these are beneficial to writers as well, it only requires the commitment of established members.

But what about competition? By helping out another writer, are you only helping the competition?

A number of authors argue that the idea that writers compete with each other is a myth. In an article for Killing the Sacred Cows of Publishing, Mr. Dean Wesley Smith points out that each book stands alone. Want to get noticed by a publisher? It’s not a question of being better than another writer, it’s a question of writing a book that stands out based on its own merits.

For a second perspective, Mr. Jonathan Maberry highlights the help that he received when he was starting out (from authors such as Ray Bradbury and Richard Matheson no less!), and the resultant view that he should in turn be generous and helpful to other writers. As Mr. Maberry states in the Jul / Aug 2016 issue of Writer’s Digest,

For a writer, the practice of mentorship – or at least the principles upon which mentorship is based – can be applied at any level to learn, share experiences, and foster community. Yes, writing can be a lonely endeavour and aside from all the mentorship in the world, ultimately an author has to sit down at the blank page or the monitor and do their work. But in between, reaching out to others – and helping where possible – is a great way to apply the principle of mentorship to the business of writing.

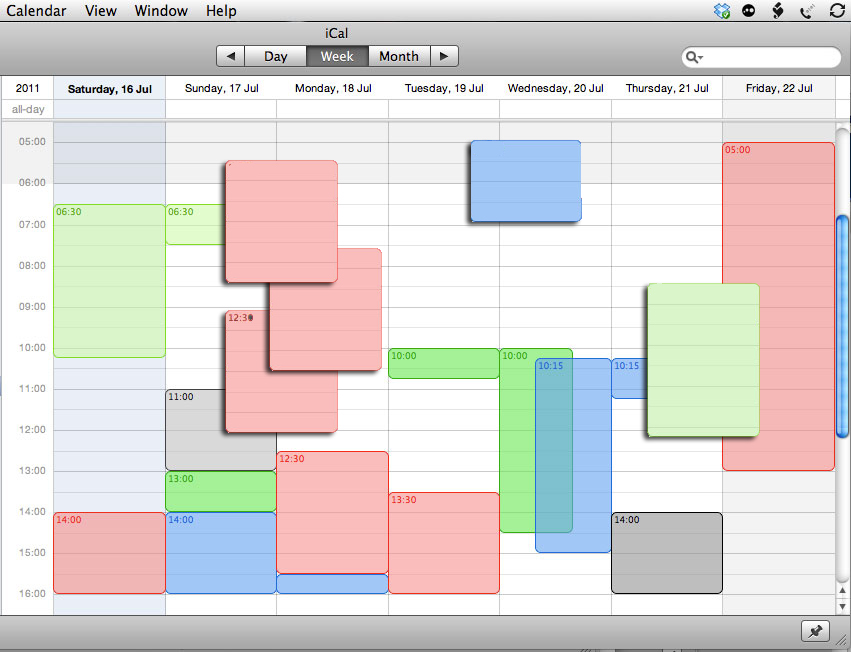

Just don’t forget when arranging meetings that somebody still has to play calendar Tetris to get the schedules booked.