I remember one After Action meeting I participated in during an overseas deployment. The mission had been simple – secure a compound – and the plan was about as straightforward as it gets. A section of soldiers would pre-position itself near the gate of a walled compound, conduct an explosive entry on the gate, then enter and secure the compound. Easy, peasy, right?

Except, when the section staged near the gate, it was open. So, they just walked in.

Another section that was sitting in for the After Action began laughing. “If it were us, we’d have closed the gate, then blown it, then entered the compound.”

We all had a good laugh, but arguably, the second method would have been just as effective at securing the compound. But, would it have accomplished the purpose, or intent, of the mission? It all depends on how the intent was communicated, which brings us to the second principle of leadership that we’ll apply to the business of writing.

Clarify Objectives and Intent

For the leadership theory buffs, I believe the current principle evolved from, ‘Make sure your followers know your meaning and intent, then lead them in the accomplishment of the mission.’ While I generally like the earlier version of CAF leadership principles, in this case the new version is an improvement. Meaning and intent are essentially the same thing, and the overall aim of leadership in the military is to accomplish a mission, so the latter half of the original principle doesn’t add much.

But Clarify Objectives and Intent? That’s got a ring to it.

Tell people WHAT you want done, not HOW to do it.

From a military perspective, this principle is about giving a clear picture of the desired outcome, or the purpose of doing something. It’s part of the command philosophy of mission command, which is built on understanding a superior commander’s intent or what they want done. Of course, understanding works both ways; commanders must express their intent in a way that can be understood.

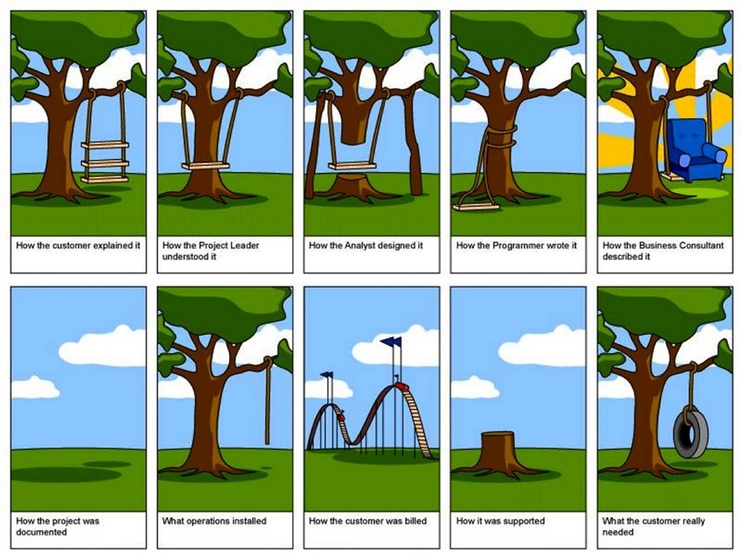

There’s much more to mission command, but for the purposes of this article, it’s enough to know that communication is kind of important since that’s how orders and intent get transmitted, in either verbal or written format. And then the fun begins as subordinate and parallel organizations interpret orders based on their own contexts.

It’s like the old joke about how different services would secure a building.

- The Navy would lock the doors and turn out the lights;

- The Army would surround the building with defensive fortifications, tanks and concertina wire;

- The USMC would assault the building using overlapping fields of fire from all points on the perimeter; and lastly

- The Air Force would take out a 3-year lease with an option to buy

Channeling my inner Buzz Killington, these are actually all valid courses of action depending on what was intended by the word secure. But again, this is a leadership principle in a military context, which is about getting something done.

How does one clarify objectives and intent in writing?

Theme

I’ll shamelessly return to the Steven Pressfield well and suggest that in writing, theme embodies the intent. After all, theme is what a story is trying to communicate, which is probably why Mr. Pressfield is so adamant that anything off theme should be cut.

Consider this.

|

In Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t, Mr. Pressfield says that a story is about a problem. What’s the solution to the problem? The theme. What does Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park tell us? ‘Don’t Mess with Mother Nature.’ Meanwhile, W.P. Kinsella’s Shoeless Joe tells us to ‘Follow Our Dreams.’ Shawn Coyne elaborates on theme in his article, What it Takes: The Vision Thing. Essentially, theme is the central guiding aspect of communication, potentially impacting everything from individual scenes to the design of the book cover. Theme is everything; it’s the controlling idea, the purpose of the whole story. |

If you accept that theme is the purpose behind a writer’s work, the intent they’re trying to achieve, then what are the objectives? In the military, objectives are the individual goals that tell a commander when they’ve achieved their intent. If the ultimate intent of Operation OVERLORD was the total defeat of Germany, then one objective would have been to secure lodgement on the European continent, or in other words, establish a beach head. Objectives are how the intent is accomplished.

So, too, can objectives be used to achieve the intent in writing and I’d suggest that the objectives are the 3 Act structure, particularly as articulated by (you guessed it) Mr. Steven Pressfield. To adapt Mr. Pressfield’s model, each story has three objectives. The first objective is to hook the reader, Act 1. The second objective is to build tension, Act 2. The last objective is to bring it all together, the payoff, Act 3. Communicate these objectives effectively, and the intent, or theme, should be accomplished.

Some Notes About Theme

I’ve read more than a few writing books that talk about theme, and a lot of them say not to worry about it all that much. Yes, the authors acknowledge that theme is important, but often suggest it will emerge as the story takes shape. Notably, these authors rarely specify how this will happen. From what I can tell, Steven Pressfield and Shawn Coyne are two outlier voices who stress the importance of nailing down theme early on.

The problem is, theme is hard. What’s more, I don’t think a lot of people come up with stories by way of theme. Instead of saying, ‘hey, I want to tell a story about how people shouldn’t fool around with genetic modification,’ they say, ‘you know what would be awesome? Real. Life. Dinosaurs. That bust out and eat people.’ Well, maybe Michael Crichton is a bad example, but I think you get the point.

|

But what’s the alternative? Not think about the intent / theme at all? What would be the effect of using military force on an adversary without knowing the overall purpose? Check the history books, there are tons of examples. Better yet, refer to Carl von Clausewitz’s On War, who wrote, ‘The first, the supreme, the most far-reaching act of judgement that the statesman and commander have to make is to establish by that test the kind of war on which they are embarking; neither mistaking it for, nor trying to turn it into, something that is alien to its nature.’

|

Heady stuff, and equally applicable to writing. In short, if a writer doesn’t know what their story is about, how can they set up the payoff? Perhaps Clausewitz could be adapted as follows: The most far-reaching act of judgment a writer must make is to establish the kind of story they are telling, neither mistaking it for, nor trying to turn it into, something that it is not.

Bottom line, clarifying objectives and intent is one of the most important issues a writer should tackle.

Next week, we’ll apply the third CAF principle of leadership; Solve Problems and Make Timely Decisions.