I’ve received a lot of useful advice, particularly when I worked as a book reviewer for a national newspaper and was lucky enough to meet some of the titans of the written word, three of which are quoted below. In their alternative worlds, they were really commenting on us in the here and now but through the lens of places and species they’d invented. They got it right, not always but more often than the rest of us.

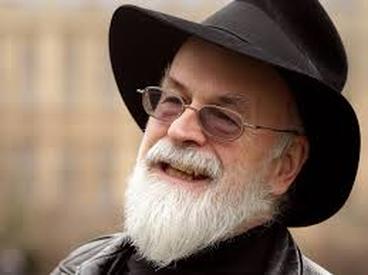

“In a world where all the Elves sing, I’d want to write about the tone-deaf one” (Terry Pratchett, Roots). His critique of Tolkien was another way of saying the same thing: “All the good ones are light and all the bad ones are dark, so where’s the grey area? Where is the orc who’s got a conscience?” I think it’s good to avoid polarisation, working with yin and yang wherever possible so each has a little of the other within.

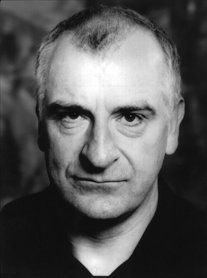

“He [Richard Dawkins] attacks his targets too hard to win hearts and minds” (Douglas Adams). Douglas’s wife later said to me that he did question the ivory towers of the establishment but preferred to reveal them from an unexpected angle, with humour. Looking at the world in a different way prompts the reader to ask and then answer their own questions. Douglas also said in Digging Holes in Popular Culture that he didn’t just plonk in some magic to solve problems, like one of those scenes where they say ‘in one mighty bound he was free’. He needed to find a way for the artifice to be plausible and somehow within the physical laws of the Universe, whether a current or future interpretation. I think that’s worth applying.

Here’s a final piece of really good advice on improving your manuscript’s quality, which I remember reading in an interview with The Master, P.G. Wodehouse, a wordsmith who toyed with language until it became poetry without the rhyme: Clear all the pictures off the walls of your largest room and lay out the pages of your manuscript on the floor, along the bottom of the wall. Imagine the top of the wall is the highest standard you can reach and the bottom is the first draft. Then, pin (or tack) each separate page on the wall at the level that it deserves for the quality of the writing. When you’ve put them all up, start re-writing the lowest pages to move them up the wall. When all of them are at the top, take it around to your publisher.

Another good idea, if you happen to be based in the UK, is to join the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society (ALCS) and register with the Public Lending Right (PLR) authority, as this won’t cost you anything and they will pay you royalties on the use of your published work.

It’s important to decide whether your protagonist is pro-active and takes the reigns of your story, agitating to change their world (Ian Fleming style) or whether they are an everyman character, a pawn that the gods pick on and torture for their own amusement (Arthur Dent style), perhaps becoming an accidental catalyst but without fully understanding what’s going on. Personally, I prefer writing the everyman protagonist because I cannot bring myself to pander to the self-assured hero role without sending it up. Whatever you choose, don’t let one type morph into the other type as the book progresses. Keep them in character!

Find your voice; and then your characters’ voices. When you write your first serious attempt at a novel, you might have no idea what your ‘voice’ is. You might even start by writing like someone else because you have been influenced by them but bear this in mind: You can’t be that person and have their success because the job is already taken. In my view, you can categorise most fiction writers into either those good at description (Mervyn Peake, Karel Capek) or those good at dialogue (Douglas Adams etc.). Yes, I know there are those that do both (Terry Pratchett, JRR Tolkien, Jaroslav Hasek) but for purposes of illustration this holds true for the clear majority of fiction writers, so you should discover early which type you are. Try writing a dialogue or continuing one you’ve overheard. Can you do it or does it dry up? Does the conversation continue, so you never run out of the lines that come next? Is it witty, imaginative and with each word or phrase dropped in with the precision of a haiku? Can you take a single quote or line out of the dialogue and any reader would know exactly which of the characters had said it because only this kind of person could have said that? If you can, you’re a dialogue writer – which means any media format is at your disposal. You can transcend platforms and take your imagination anywhere you want. You don’t even need to describe your characters because the reader paints a picture of them in their mind just from the way they speak. Do you know that Pratchett never bothered to describe the character Granny Weatherwax, yet every reader can describe her to you, often differently? Dialogue is less likely to be associated with literature but when you ask someone to quote their favourite line from a novel, it’s usually a spoken piece.

It’s extremely useful to find out if you are a verbal thinker or a picture thinker (look this up). I’m a verbal thinker because I play with language all the time, invert it and subvert it. ‘You’re back?’ ‘Yes, she nearly trampled it.’ Although this line isn’t great, a picture thinker could never have come up with it. A picture thinker on a desert island would be bored quickly because they need input. A verbal thinker could live in isolation for years and keep themselves thoroughly amused by the words in their head. In my experience, the fastest, wittiest and most imaginative or surreal verbal thinkers generally have bi-polar disorder to some extent or other. ‘The miseries’ affected Spike Milligan, Douglas Adams, Tony Hancock and many more writers and artists now too famous to remember. Comedy comes from pain sometimes, the self-destructive impulse that can fascinate, but a writer or painter seeing the world in an unusual way is also a glittering gift to all around them.

Why do you remember the words of a song? It’s because they follow a sing-song pattern in your head. Now take a look at the prologues of The Hitch-hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and of The Restaurant at the end of the Universe. They lilt up and down like a wave-form, flowing like a song. People would say it reads well and it’s very easy to memorise and quote. Why is that? It’s because of the pattern. Even with jokes, you might spot a pattern of three which sets up the absurdity: ‘… famous space ships the GSS Daring, the GSS Audacity and the GSS Suicidal Insanity.’ There’s also the cut back and reveal – the finest example being Doulas Adams’ Kamikaze sketch. If you can become a master of pattern, you’ll be very readable.

I apologise for bringing comedy into this so often but that’s my natural writing angle and maybe I can pass on some experiences that a horror writer, for example, can’t. Comedy writing in particular can be silly and even cheesy, lulling the reader into a false sense of security so you can drop in a very serious point to make the audience re-evaluate themselves. Comedy has a kind of power in that way which aligns it to criticism but there’s a difference. Every monarch needs their fool because other people aren’t brave enough to correct them; and that goes for governments, societies and cultures too. Comedians provide a service. Stewart Lee wrote about this in The Perfect Fool, where the shaman of the Hopi Indians have license on one day a year to humble arrogant members of their community because that’s healthy. This is no different from King Lear but has developed in a culturally and geographically removed location. We have an inner need to make our people think again, to limit madness, so the way we naturally do it is to make fun of those that over-step. What safer option is there? Comedy has to say something new though, to create, or the audience will return to the old comedians and their recorded material.

The difference between an outright critic and a comedian is best exemplified by the ancient Greeks and their Cynical School of Philosophy. The origin of the word ‘cynic’ refers to a yapping dog, as these people stood in the market place and just criticised without offering anything alternative in its place. A food critic, for example, doesn’t need to know how to cook. With comedy as social commentary, the crowd will actually pay you to hear it, if you’re good enough, but you must deliver original ideas within the angst or your material will never be performed (see Timon of Athens by William Shakespeare, or rather don’t).

Another question for comedians is – What is funny? As the Monty Python team ruled, once you start analysing a joke it isn’t funny anymore. Interestingly, Ricky Gervais claimed no sacred cow should escape – he’d write jokes about anything as long as they were funny. The interviewer asked if he’d make jokes about disabled people and he said ‘No because the subject isn’t funny.’ To his credit though, when he did think of disability jokes that were funny (some made the audience confront their attitudes to disability), he did use them. Most writers wouldn’t be brave enough to go through with that but, then again, we can’t all be Derek & Clive.

On the subject of offending people, or trying not to, have you thought about casting issues in any great depth? Some authors are aware of quotas and many opt for the formulae of casting the main character’s best friend from a different ethnic background. They will then act as the heroic rock throughout the piece because the writer is too scared of criticism to give them a personality flaw. Boring. Why not bring your work to life by the simple and ingenious trick of (dah, dah, dah) never actually mentioning race or colour? Then if any director of the future comes to fill the roles, none of the casting decisions will have been pre-determined. Anyone can take any part and, think of this as the bonus material, you will have written more rounded characters who have not been turned into plain sounding-boards by the author over-compensating to ensure what they’ve written is beyond criticism. That’s why the bad guys in films are usually English because that’s the only nationality available that doesn’t mind. A hundred years from now everyone will be colour-blind anyway, so drop it and focus on something more interesting and unusual about your characters instead.

Any writer worth their blotter will take notes of things that occur to them: mannerisms, things they’ve heard or seen, a line that encapsulates a character, then squirrel them away into a sock drawer or onto a growing mole hill in their study with a view to one day using the material. The post-it notes, beer mats, shirt cuffs, inside-out match boxes, receipts, bus tickets and ripped shopping lists with scribbles on the back will need to be filtered properly but they are gold. They have value and should be treated as if they represent money lying around. When an author comes to type it up, some will fit into this idea and some will be kept for another idea or genre but remember that the paper bits will go in the bin, so back up the computer file and save a copy separately where no one will over-write it. If you buy a new laptop and transfer your part-written book to it, back that up separately too because most hard-drive failures happen in the first month, as mine did (Packard Bell, are you listening?) and took 36,000 words with it to the bottom of a very dark sea made of whisky where you don’t feel like trying again for a long time. Back it up!

The great philosopher Shahid Afridi once said “I won’t change my style; they should change their thinking”. The reason I mention that is, if the fashion is teenage vampire romance, or whatnot, don’t feel that to be published you must follow fashion. Write the genre you’re good at writing and wait for fashion to come around to you. If that happens and you have several books to your name, the readers will want to collect your back catalogue as well. Don’t sell out to trends as you’ll only ever be an imitator.

Breaking genre and stereotypes is a healthy temptation but do be careful when you’re messing with the narrative imperative. No matter how often you’ve heard it, the right boy gets the right girl at the end is the hard-wired law of the story because it’s what the reader was brought up knowing. The knight kills the dragon and marries the princess is comforting at a subconscious level, so if Harry doesn’t whisk Hermione off into the sunset, they feel it’s a bit raw.

Another thing to think about is the kind of book format should you push for. People who collect books and pay significant prices to get them will always go for the hardback first edition in dust-wrapper. However, the author doesn’t get a cut of the re-sale price of a book and will probably have a better income producing paperbacks, with a lower production cost. Are you writing a book to last 200 years, to sit on your shelf at home and to command a respectable re-sale price on Bookfinder (a hardback), or do you want to maximise your chances of making a living as a writer and you don’t care if it falls apart after it’s sold (a paperback). Really, the question is whether you feel a book is a legacy item, an antique, or whether you have a less physical attachment and think the words don’t care where they’re printed. That’s your choice, money or pride.

Then we’re onto legacy. Even if you don’t make anything from writing, isn’t it an exceptional achievement to know that what you’ve written, ideas you’ve framed and humour that you’ve thought of will enter into the cultural record of the human race and will be there forever? Your descendants a thousand years from now can find out what was in your head and they can smile as they read it. Why not invent one new word in everything you write, so if it catches the public imagination you will have made a contribution to language itself? Making your mark on history has got to be worth something. Imagine if we had a longer record behind us could understand ancestral thoughts, their delights, their sadness and their witty jokes about the Romans. Say something worth preserving for a thousand years because that’s inevitable anyway, as soon as it’s in print. If you say anything ugly, prejudiced or which turns out to be politically on the wrong side of history, bear in mind that your ancestors will read that too and form their own opinion about you. If you must, remember that the most prolific author of all time was ‘Anonymous’.

I don’t get writers’ block, I never do. I never run out of something to say (my wife says I’m building up a really good tolerance to the powdered glass) but I know people who used to have this professionally debilitating affliction and, as the saying goes, stared at the keyboard until their forehead bled. I read that someone once said to Peter Cook “I’m writing a book” and he replied “Neither am I.” As you’ve probably gathered, ‘used to have’ means they found a workaround. Picture this: You’re stressed at not being able to start writing because your mind is blank, the distractions are there already because your workplace is your home (fridge, tea, bath, TV, exhilarating dip of your head in the fish tank) and you know you need to write to earn to pay little Timmy’s matador lessons and if you don’t your family will think you’re a fraud and a failure, so the stress increases on you to write right now, which sends you back to the fridge and the cycle repeats. You should have seen Robert Newman after a year of writing. Try this: Go to an antiquarian bookshop (for this exercise forget libraries – too much modern tat) and pick up something really archaic, preferably something Victorian or eccentric. Read a few pages to put yourself on a path and then imagine bringing the concept and characters you’ve just followed into the year you’re living in, to create a modern analogue. This is the pilot light to your boiler and it should fire up a string of original thoughts. You’re not copying the book; you’re waking up. You’ll see ways to add scenes to your story or perhaps even re-imagine the entire plot. Even if you aren’t influenced by the pages of the old book, you have been switched ON.

Did I mention influence? If you want your writing style, subjects and pattern of speech to be unique, you would be best advised to guard against subconscious influences as far as possible. The main one of those is television. We’ve got a TV at home for playing an occasional DVD but the aerial hasn’t been connected for about 8 years. That way, it’s much less likely I’d ever write a script or character that’s close to one already being performed. I can write about the world in my own way, not yours. It also reduces distraction – where you stop writing for two weeks, blink and a year has drifted past – and you will also find you read more books without watching television. Peter Terson, who wrote Zigger Zagger, used to travel the roads of Hampshire in a gypsy cart to get away from all influences. An author should read extensively before they write because the examples of what they are trying to emulate are there for anyone with enough patience to discover. My advice is to cut the signal to your television, if you can. I bet you can’t. It’s a narcotic really, an insidious saboteur that cheerfully stops you becoming a better writer.

This answer just keeps going, doesn’t it?

Marketing. I simply can’t get out there and promote my work. It doesn’t matter how good it is if no one ever reads it, that I accept, but publicising oneself is like cornering your friends at a party and asking for charitable donations. Next time they’ll cross the street, an ocean, even feign death to avoid you. I just can’t do it. Writers should write and sales people should do the selling. It’s not fair that the number of readers you have is not based on how good a writer you are but relies on other factors. If I write a script and hand it over, I’m done as far as I’m concerned. No one requires me to get on stage or at the microphone as well to play all the parts, so why is it not possible to just get on and write books? I remember Tom Holt saying he’d accepted a book signing, no one had come in or even looked in his direction, the staff had brought him cups of consolation tea like a serial loser at the bookies and that it was the most confidence crushing experience he’d had as a writer, even worse that hundreds of people saying his early work was the good stuff. Well, actually, it might also have had something to do with the lemon polka-dot pullover he was wearing at the time.

On the topic of ‘these are a few of my least favourite things’, it’s also deeply concerning for the future of creativity that sports or media people who can’t write their own books get publishing contracts ahead of people who can write. Okay, they’re famous for something else, which they’ve been rewarded for, but people who don’t write shouldn’t have their names on books and top author lists; ditto for people who can’t play a musical instrument or rhyme a lyric being described as music stars. There you go, I’ve attacked my targets too hard so will probably have to hint I only did it to re-inforce a previous point. The thing is, does cooking or having high proficiency at hitting a ball mean that person is good enough to take a writer’s place at writing? Why not select for the skill that’s relevant to the product?

This next bit is quite important, so congratulations if you’ve read this far down. I’ve submitted a script for consideration and then it’s been used without my name on it. Three other writers I know suffered the same thing. That happens a lot nowadays because television channels and production companies employ in-house writers who can hold onto their jobs only by consistently delivering original ideas and killer lines. Clearly, it would be difficult to sustain brilliance over the course of a career, so it isn’t just laziness, but the least morally scrupulous end of the spectrum can dip into the pile of unsolicited or solicited (e.g. BBC Talent) submissions for inspiration. Occasionally, although it has happened to me, a show will be broadcast with 90% of the content you’ve sent them and just have the ending re-written. Ouch. The other thing that’s changed, of course, is the name of the author it’s been attributed to. Then, when you contact the company to ask what’s going on, they will reply “Can you prove when you wrote it?” If you can’t that’s your lesson learned. “It’s not possible to own a joke” – arguably true, unless it’s published already and more than 9 consecutive words are the same but it won’t be published already because, if it was, you wouldn’t have sent it to them. To protect yourself, emailing your manuscript is not enough. You need to either go to a public notary and pay them about £30 to stamp it and retain a copy or you should post a copy to your solicitor by a recorded method of delivery on the understanding they keep hold of it and don’t break the seal. It’s annoying that writers have to protect themselves from intellectual property theft but, even if we can’t expunge the practice, we can at least apply safeguards. Protect yourself!

Every modern thriller has American characters in it. No offence intended but there are 199 countries/nationalities in the world guys, so why only use one? For that matter, why do UFOs always land in the same place? There’s also a Special Forces colonel who comes out of retirement and then sustains a very small cut on his cheek to indicate he’s suffered but isn’t serious enough to spoil his looks on the publicity material, the male authors can’t write convincingly strong female characters, sooner or later everyone’s a ninja, no one can just be friends and the problems so carefully constructed in the plot are finally resolved with hand-guns because the author can’t think of any other way to do it. Even in a country where no one has handguns because they’re illegal, they’ve all got handguns. There’s probably some gunmetal tree they grow on.

Maybe it’s just me but as soon as one of these motifs appears, the dialogue sounds wooden before I’ve even read it. Please, please, please let me do something different. I want to try to write just one book with no pistols and no Americana in it, just to see if any writer on this unoriginal blithering planet can be the very first to do it. Actually, I advise you to ignore the list of tropes that I’ve just given and start logging a few of your own. Corsets in historical romances perhaps, or butlers in the 1930s – did even one in five thousand houses have a butler? What about aliens which follow the Earth vertebrate design (5 to 6ft tall with symmetry down the long spinal axis, four limbs and a head at the top that does the thinking, so the author doesn’t have to). Whatever you can identify as a recurring motif in your genre, be aware of it and be original by deliberately not using it. The Andalusian stencil-salesgirl revenge artiste who gets stuck in a rut because the new wave of plastic stencils won’t take a proper slicing edge and who eventually gets defeated in an unexpected warehouse mango-mountain collapse that she can’t stencil-slice out of would be a lot more interesting than yet another former secret agent with yet another automatic yawn who solves any problem in life by popping holes in it, believe me. I’m not against shooting either; I’m against formulaic reinforcement. Pass a mango. No, not the one they couldn’t get down from the tree without shooting it.

Structurally, I completed Lightspeed Frontier in 11 weeks and it came out at 62,500 words. That’s quite a fast story for me, as I also have a day job at the University that needs plenty of attention or the scary bugs might escape and eat the public. I wouldn’t have chosen lightspeed as one word but am conforming to the title of a larger project. My style is modular, to prioritise the imaginative chapters I want to write and then bridge any continuity gaps at the end, i.e. how they got from this place to there, so the final pieces are generally the least-best stuff because all the good ideas and snappy lines are already down. It might be called Lightspeed Frontier, which is the name of the new computer game that this material is supposed to populate, cross-platform style, but if the game designers who are reading the manuscript this week say it’s too different to their vision, it will probably be called Out of This World, or something like that. I’m probably the only writer who would complete a book in full and then find the title.

It will make a good screenplay, so tying it to a game then raises the question of whether the author owns the film rights or, if ‘we’ own them, more likely but how much of ‘me’ is in ‘we’? The script has to be written first of course, so I’ll start that conversion soon, although I’m helping anonymously to re-write someone else’s screenplay first. When you’re converting a book into a script, the first thing to do is highlight all the best lines and, whatever else you do, make sure they are in the script. If you are turning someone else’s book into a screenplay, remember that the reason it’s good is because the original writer came up with classic lines, so don’t replace the brilliance with your own material to make your mark and think the audience will accept it; just give them the book they love and the lines they need to hear but make it more visual.

I’m not going to try a synopsis because this book is way too eccentric to conform to classification. I think my modus is best described as putting together a framework to hang sections of things that amuse me onto, so if even a few percent of those lines or scenes are liked by the reader and each reader enjoys a different selection, it was worth creating. Although I could say it is comedy dialogue science fiction that’s idea-fuelled, intelligent, sexy and informed, with a love triangle, a love quadrangle and a burning tortoise who determines grant applications, I don’t think I will because that doesn’t begin to make sense of it. This book isn’t like anything else ever written in sci-fi, I think it’s funny and my wife won’t like the cover, so that’s the first three boxes ticked. If it predicts any aspect of our future or makes anyone laugh and then perhaps stop and think, that would be even better.