General Dwight D. Eisenhower is reported to have said that, “What is important is seldom urgent and what is urgent is seldom important.” As Supreme Commander of Allied Expeditionary Forces in Europe during the Second World War, and later as 34th President of the United States, Ike had lots of experience in prioritizing what tasks would get performed in a day, an enduring complication of war. Take Afghanistan for example.

A quick list of things to do in a counter-insurgency could include, but not be limited to: meeting with the elders or local power brokers; assisting in building local infrastructure such as roads, wells, or schools; delivering humanitarian supplies; providing medical support; training host nation military forces; training host nation police; resupplying own troops; fixing and maintaining vehicles and equipment; providing for own security; patrolling – making sure to mix up the routes and times; planning, giving, and receiving orders; conducting rehearsals (always the first thing to get cut); while underway, conducting fives and twenty-fives and any other type of drill; protecting VIPs and putting on dog-and-pony shows whenever battlefield tourists come over to improve morale; talking to locals; assisting other agencies; having Quick Reaction Force on standby; and by no means last, fighting, in this case, the Taliban.

Even with a large force, even a blind person on a galloping horse can see that the numbers get eaten up very quickly. And while arm-chair generals can talk about the ‘tooth-to-tail’ ratios all they want, at a certain point equipment still needs to be fixed, planes still need to be loaded (considering Afghanistan is land-locked), and operations still need to be planned and coordinated. And no different than military operations ever, everything needs to be done yesterday.

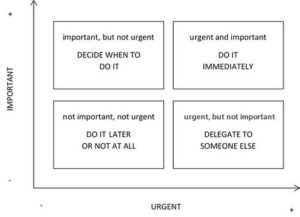

All of this is a-okay, except for the inherent risk when over-tasked in that when trying to do everything, often nothing gets done well, least of all the tasks that matter. Emergent prioritization sometimes results, with corners invariably being cut. That fifteenth or twentieth patrol doesn’t do its rehearsals, they just go, which is all right – until it’s not all right. Ultimately, a failure to prioritize can be an accident waiting to happen, which is why the military has a simple philosophy to deal with situations where ten pounds of tasks are being jammed into a five pound bag. The concept is the principle of war known as Economy of Effort and it’s equally applicable to an artist’s inner creative battles.

Economy of Effort

Economy of effort recognizes that ambitions always outstrip resources, which necessitates prioritization to ensure that enough resources exist to affect the top priorities. The principle involves identifying a main effort, or top priority, and assigning the necessary amount of resources needed for its accomplishment, while devoting minimum resources to less important tasks. In this way, economy of effort is symbiotically linked to the principle of concentration of force, because to ensure we’re able to hit the adversary with superior force at a decisive time and place, we may need to accept some risk in non-decisive areas.

As suggested by the economic language of the principle, economy of effort also encompasses the law of diminishing returns, or the concept that a continual increase in effort does not lead to a continual increase in results. In other words, in a world of finite resources and time, decision-makers should apply their resources in areas where they get the most bang for their buck, while also ensuring they have enough for their most important tasks.

Like all the principles of war, this one is dependent on knowing what you’re trying to accomplish, which is the first principle of war, Selection and Maintenance of the Aim. Once an aim is chosen, a plan or strategy will determine where the main effort is (something that directly influences achievement of the aim) and just as importantly, what are the secondary or tertiary supporting efforts. Some activities will directly lead to accomplishing the goal, others will not. In military terms, some activities will be mission essential or mission critical, others will be mission enhancing. This difference will make it possible to prioritize, which in turn, will help dictate where resources get used.

Applying the Principle

To apply this principle to an artist’s inner creative battles, first start with the aim, which in this case is to conduct the artistic endeavor, or to write. The act of writing itself is therefore the main effort and where our concentration of force should be aimed. This is useful in that it shows where the preponderance of effort should be applied.

For the sake of argument, what types of activities directly contribute to achieving the goal of writing and which don’t achieve that aim? At a strategic level, or the higher artistic level where the goal is simply to be a writer, anything not directly involved in writing doesn’t accomplish the aim, so activities like building an author platform are secondary. From this perspective, economy of effort would suggest that a prospective writer should never let their social media activities in support of building an author platform detract from their ability to write. Put simply, don’t be on Facebook when you should be writing. And yet, this is an all-too-real outcome given the current importance placed on author platforms, which are evidently quite important if a writer wants to get published. So what to do then?

Even here, economy of effort can be applied. Yes, there are no end of articles and books on the importance of author platform these days, but most of this literature also recognize the crowded landscape. Between Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, Google+, Instagram, Goodreads and many others, an author could easily spend all their time chasing likes and retweets. Before long, no time would be available for writing and as important as it is to have a social media following for the business of writing, if it consume the time available to actually write – something that directly achieves the aim – then the cart is definitely before the horse.

The answer is straightforward and contained within the fact that while many commentators on author platform exhort writers to get a social media following, they also almost universally acknowledge that it’s better to do one or two platforms well rather than all of them poorly. Or conversely, all of them and no writing. So pick a few platforms that are interesting and that can realistically be done well and forego the rest. This is the essence of economy of effort; being judicious with supporting activities in order to concentrate fully on higher priority activities.

As much as the military had a thousand and one things to do in Afghanistan, economy of effort was very much still applied; whenever the Taliban popped up, everything else was dropped so they could get thwacked. Sure, maybe a focus on the enemy wasn’t the right overall aim for Afghanistan – some might argue that the focus could have been more on the populace than on the adversary – but it was the aim at the time and everything else got economized and prioritized to support that aim. Fortunately, as hard as it sometimes seems, pursuing an artistic endeavor is in many ways a much simpler pursuit than running a counterinsurgency.