|

When’s the last time you started something new? One of the joys of having kids is seeing them try new things every day. When they accomplish something they’ve never done before, it’s amazing. What often goes unseen, however, are all the times they’ve tried before, the practice attempts.

Let’s take brushing your teeth as an example. My daughter sees me putting toothpaste on my toothbrush and thinks it must be the easiest thing in the world. When she tries to do it, it’s not quite the same result and she gets frustrated. |

When it comes to writing on the other hand, I’m anything but a big deal.

Interestingly, even though I’m new to writing fiction and I recognize it’s highly unrealistic that I would be good at it when I’m just beginning, I go through all the same emotions as my daughter. I write something, it’s not quite what I was looking for, and I get frustrated. I forget that before you can run, you have to first learn how to crawl and then walk.

Now I get it – that observation isn’t exactly rocket surgery, but humour me a bit longer. As a student of many things, I think this lesson is always worth refreshing so as to not inadvertently sabotage whatever journey of improvement you might be taking. To do so, I often turn to George Leonard.

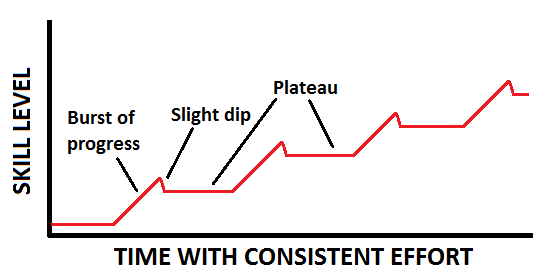

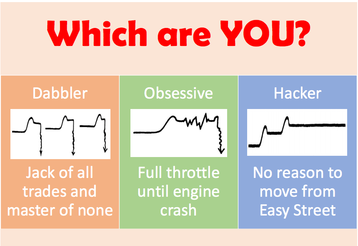

Dabbling, Obsessing, Hacking. Leonard defines three types of self-sabotaging behaviours. Dabblers love starting new activities and initially make good progress, but rarely stick with something when it gets tough. Obsessives are all about improving as a bottom line – they’re going to make progress no matter what, but often trade fundamental learning for quick results. Lastly, hackers are happy making a bit of improvement, then staying on a plateau forever. In the long run, all of these behaviours can lead to people stunting their long-term improvement.

Keys to Mastery. I’m always somewhat skeptical about claims like, ‘7 Tips to be Your Awesomest You,’ but it’s hard to argue with most of Leonard’s tips, like practice. Want to get better at something? Try practicing…ah, it’s all so clear to me now.

Other keys are easy to understand, but difficult to execute, like surrendering. For a new writer, are you prepared to write a first novel (let’s say a year worth of writing and editing) and potentially have to surrender to the fact that it’s actually not very good? That maybe that whole year was simply one big learning experience in what not to do? I feel like I’m facing that very scenario right now with a novel and to reference some advice from Mr. Stephen King, let’s just say that it’s easier to talk about killing your darlings than to go ahead and place their heads on the chopping block.

Still, I think the most useful of Leonard’s keys to mastery is instruction. Simply stated, there is no substitute for first-rate instruction, especially the feedback. Depending on how efficiently you want to improve, taking a course or finding a mentor is almost a must. And of course, ensure to take credentials into account.

Homeostasis. Leonard has lots to offer, but in the interests of brevity, the last concept I’ll mention is his take on homeostasis, or resistance to change. What immediately struck me was how Leonard’s characterization of homeostasis is very complementary to Steven Pressfield’s idea of Resistance. This extends to Leonard’s proposals on compensating for homeostasis, to include:

- Establish a daily routine. While important, Leonard stresses not to go overborne at the start. If you’ve never written before and you’ve resolved to write for 2 hours a day, that might be a hard resolution to keep.

- Develop a support system. Leonard diverges from Pressfield in this regard in acknowledging the importance of others as a step to overcoming homeostasis, particularly those who’ve been down a similar path. For aspiring writers, there are tons of great websites and writing support networks, or you might have luck with a local writers group.

– George Leonard. Mastery: The Keys to Success and Long-Term Fulfillment

And one day, I’ll be walking.