Popular culture is full of stereotypes about military personnel as loud-mouth toughs, intimidators who browbeat their subordinates into obedience. Whether it’s Gunnery Sergeant Hartman in Full Metal Jacket, or Command Master Chief John James Urgayle in G.I. Jane, the characterization of a soldier as a hard-ass tormentor intent only on breaking somebody down in order to subsequently build them back up persists.

Of course, there are good reasons for those stereotypes. After all, R. Lee Ermey actually served as a drill instructor in the US Marine Corps prior to deploying to Vietnam, so it’s safe to say his method acting was based on solid characterization.

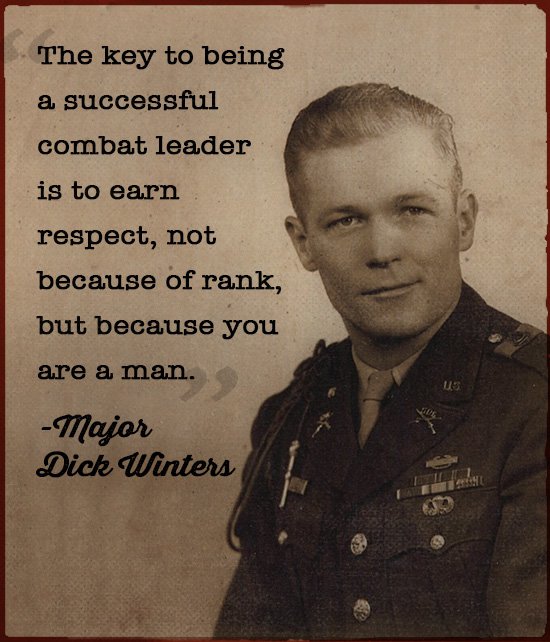

Unfortunately, given the vividness of these roles, it’s easy to lose sight of the other side of military personnel, the ones whose subordinates, when told to plan for the invasion of hell simply pack along some extra canteens of water and a couple more bandoliers of ammo. Dick Winters in Band of Brothers, or Sgt. Matt Eversmann in Blackhawk Down – these are examples of soldiers whose regard for their subordinates is matched only by their tactical prowess.

Treat Subordinates Fairly; Respond to Their Concerns, Represent Their Interests

The previous version of this principle was, ‘Know Your Soldiers and Promote Their Welfare.’ (Or, the oft-quoted classic from the school of Warrant-ology of, ‘Know Your Soldiers and Put ‘Em on Welfare.)

I like the updated principle, but for the first time since starting the series, I feel like an important idea was lost in the revision. Nowhere in the new principles does it say to know your subordinates, and while it could be argued that this is implied, to me it’s important enough that it should be explicit. If people really are the military’s most valuable resource, it would seem the least a leader could do is get to know the people under their command. In the end, it’s not a resource that makes the ultimate sacrifice, it’s people.

This aside, the current principle does still address the underlying theme of looking after your people. More specifically, this entails a relationship based on genuine concern and respect for people and their conditions. The principle isn’t saying for everybody to be friends – far from it, and I’m a big proponent of the maxim that leaders should be friendly, but not be friends – but it does recognize that people are unique and should be treated as such.

The Three Planes of Well-Being

The publication, Leadership in the CF: Leading People, recognizes that there are a number of different ways through which subordinates can be taken care of, manifesting in the physical, intellectual, and emotional planes.

On the physical plane, looking after your people means making sure they’re fed, clothed, and sheltered, that they’re physically fit, and that they have the resources needed to do their jobs. On the intellectual plane, this is about giving them the training, education, experience, and self-development they need to perform in certain conditions. Lastly, on the emotional plane care is demonstrated by treating people fairly and with respect.

These are all great points, but as with the other leadership principles, how can this be applied to the business of writing?

There are actually some very easy applications. For example, actions on the physical plane could be applied to the writer themselves. It’s a small thing, but having the basic necessities and a minimum level of fitness improves resilience and could enable a writer to better deal with some of the occupational challenges, such as the crushing amount of rejections. From the emotional plane, we could easily extrapolate the need reach out and talk to people, something that’s been mentioned on this blog a number of times. Of course, when you’re interacting with others, do so with respect and treat them fairly.

But these applications aren’t particularly new so let’s go deeper, mostly because I think the real utility of this leadership principle is the exhortation to demonstrate genuine concern for people. So let’s turn this on its head and say that this principle can best be applied through an approach to marketing. Pardon? Treating people with respect is analogous to marketing? Yes, you read that right, or more correctly, you read Tim Grahl right.

For those who don’t know, Tim Grahl is an author and book marketer who’s helped numerous other authors launch their books. In doing so, his activities range from building author platforms to book launches to marketing. Of particular note is Mr. Grahl’s definition of marketing, which has two components. Marketing is:

- Creating lasting connections with people, through;

- Being relentlessly helpful.

If this sounds nothing like what your preconceptions tell you marketing is about, you’re not alone. Mr. Grahl himself addresses this dichotomy in much of his work and it’s well worth the time to read or watch some of his work.

But there’s another thing worth highlighting from Mr. Grahl, which is that marketing isn’t about tricking people into buying something they don’t want, or even need. Instead, it’s about helping people connect with something that’s going to help them, which in this case is your work.

This latter view brings whole new meaning to how a writer presents themselves, especially if it adheres to the principle of showing genuine concern and respect for people. To make this work, a writer has to believe that their work is meaningful and that it’s actually going to benefit somebody. The benefit may only be helping someone else gain a new perspective on a particular issue, or even entertaining them for a couple of minutes, but the belief has to be grounded in perceived added value.

So what does this mean? Practically, it means know the target audience and adjust outreach behaviors accordingly. For whom would your work most benefit? Or, if the story has come first, then define and find the target audience. After that, be relentlessly helpful as a means of developing connections, which might be expressed in any one of a number of ways such as sharing content or microblogging. In the end, this is about being helpful and adding value, not trying to swindle people by selling them something they don’t need.

As corny as it sounds, Tim Grahl’s method adheres to the principle of treating people fairly, responding to their concerns, and representing their interests. If you can do this, while also fulfilling a passion to write, then so much the better. Alternatively, you could try adapting the browbeating technique, which I think would probably be analogous to flogging your work through repetitive Tweets on Twitter. After all, somebody must read those things, right? Right?

Next week, we’ll look at the leadership principle of ‘Maintaining Situational Awareness; Seeking Information and Keeping Current.’